In this thought-provoking episode, the first of three conversations in our Sustainability Visionaries series, host Avi Rajagopal is joined by John Woelfling, a principal at Dattner Architects, to discuss affordable housing and sustainability but also, more broadly, finding ways to let the best ideas in architecture serve the most vulnerable populations. First, Rajagopal sets the stage delving into the current challenges faced by the building industry, such as its significant carbon emissions, plastic consumption, labor exploitation, and unequal distribution of environmental impacts.

He emphasizes the critical role architects and the building industry play in addressing these issues, asking “How can we use our work to do good in the world?” His conversation with Woelfling follows, exploring the power of design to make positive change with examples of Dattner Architects’ evolving approach to responsible architecture—from its design of the New York City’s first public LEED-certified building, the Bronx Library Center, to its work on 8,300 units of 100% affordable housing across the city. This engaging talk underscores the importance of rethinking our approaches to sustainability and highlights the potential for architecture to contribute to a better, greener future.

Connect with John Woelfling on LinkedIn!

Moments to check out:

- John discusses Sustainable Building Practices in New York City (Starts at 9:39)

- Leveraging Passive House Building Typology to Address Environmental Inequity in the Bronx (Starts at 20:10)

- Connecting with Clients and Building Partnerships to Push the Envelope (Starts at 26:44)

Connect with our host Avi Rajagopal on LinkedIn!

Discover more shows from SURROUND at surroundpodcasts.com. This episode of Barriers to Entry was produced and edited by SANDOW Design Group. Special thanks to the podcast production team: Wize Grazette, Hannah Viti, Samantha Sager and Rob Schulte.

Avi Rajagopal: [00:00:00] Welcome to Deep Green, a show about how the built environment impacts climate change and equity. Deep Green is brought to you by Metropolis. I’m your host, Avi Rajgopal. We have a special episode for you today, the first, in a series of three conversations with thinkers and doers who are pioneering new ways of thinking about sustainability, health, and equity.

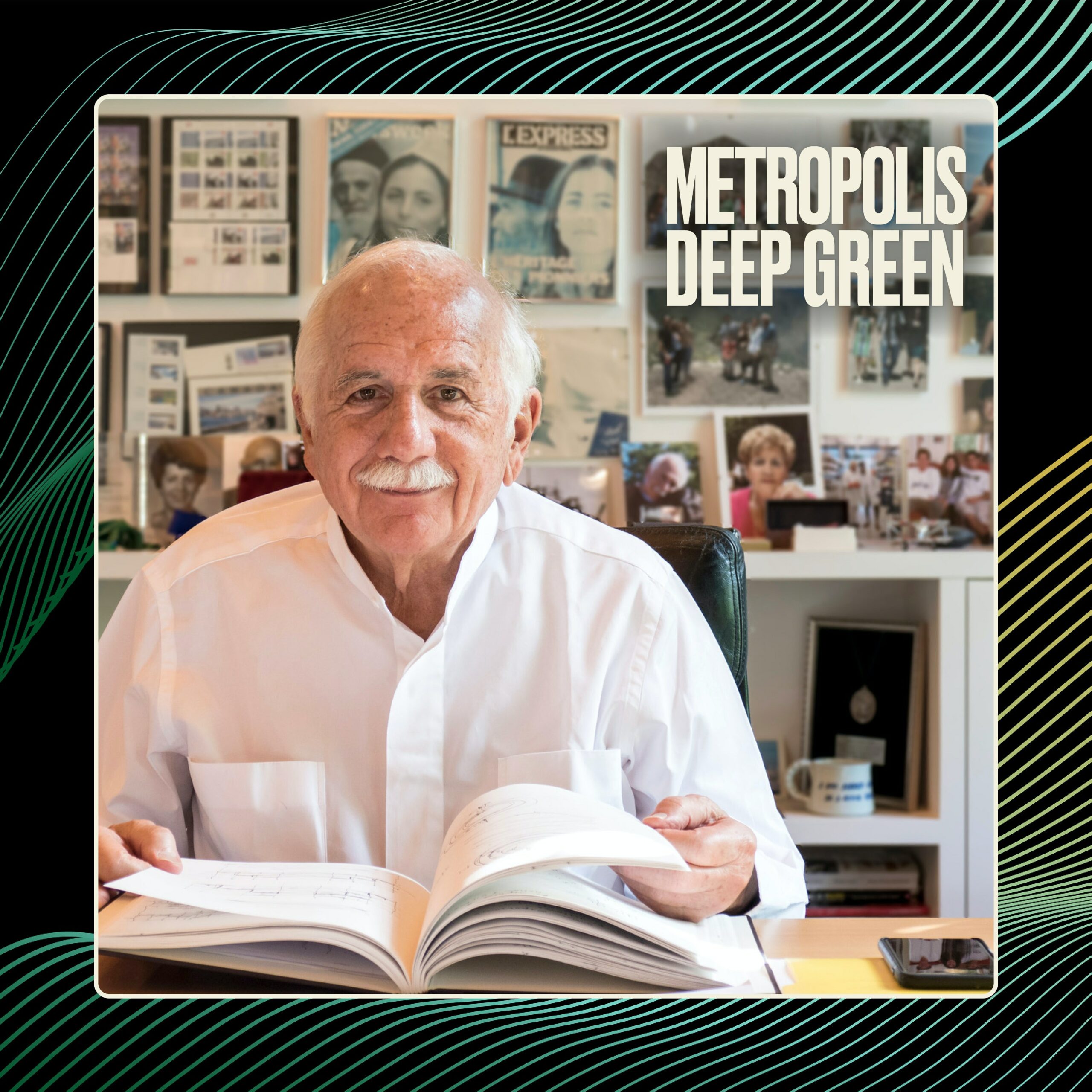

My first guest is John Woelfling, a principal at Dattner Architects in New York City. John speaks about affordable housing and sustainability, which is really about putting sustainability within the reach of everyone. And finding a way to let the best ideas in architecture serve the most vulnerable populations.

Our conversation was conducted in front of a [00:01:00] live audience at Penn 1 in New York City.

Good afternoon folks. Thank you so much for joining us today. It’s so awesome to see everyone here if you know Metropolis at all. This is one of our first in-person events in a while, so it feels great to be here with a group of people. Yes. Cheers for that. Woo.

I’m Avi Rajagopal. I’m the editor-in-Chief of Metropolis. Thank you for joining us today. Today’s event, we’re gonna have a conversation about how the thing that we usually call sustainability, which is ways of taking care of our relationship as human beings with. Each other and with the ecology of this planet is actually changing a little bit and how that landscape has shifted.

We call that concept very loosely, Deep green because we know a lot about green buildings and green fashion and green food and greenness and green that, but [00:02:00] there’s a sense that standard approaches to sustainability need to change. Right. So that’s kind of what we’re gonna talk about today. I already introduced myself with me today to talk about that is John Woelfling, who is a principal at Dattner Architects, a fantastic firm based here in New York City.

You’ve very likely you’ve used a subway station that Dattner has designed. You’ve been in a park that Dattner has designed. If you live in New York City, it’s almost impossible that you haven’t been touched by the firm’s work in some way. So we are gonna dive a little bit more into Dattner’s work, but before we do that, I just wanted to set the stage for you as to why it’s important for us to have this conversation.

So, as I said, Metropolis, we’re an architecture interior design magazine, and one of the things I think that we don’t. Always appreciate, especially those of us who might not design buildings day in and day out, is that buildings are actually some of the biggest products we make as a society, right? So, so a lot of people involved in making [00:03:00] buildings, a lot of materials, a lot of different networks, a lot of economics.

It’s just one of the most resource intensive things we do as human beings, as a society, right? And so when we think about sustainability, In general, you might think about cars and fossil fuels. You might think about air travel. You might think about a lot of other things that are in our day-to-day life, we think as.

Having a huge carbon footprint. You think of pollution, you think of water use, things like that. But weirdly, buildings are this kind of a, a node for almost all of them, and that’s what’s kind of interesting about having this conversation about architecture and among architects. In general, I’m just gonna go through some bad news for you.

If you work in the building industry, that’s what I do. Just forgive me, but I swear like everywhere there’s a huge problem. There’s a huge opportunity. So buildings are responsible for 39% of the world’s carbon emissions. This is pretty well [00:04:00] established fact. We’ve known this at least since 2003.

Metropolis did the first story on that. But there’s some other interesting things that we have to place alongside that, right? So most of the buildings. In New York City that are standing today, we’ll still be here in 2050. So if we want a zero carbon future, you might have heard of NetZero Cities, 75% of the things that we have to deal with.

In 2050 are already standing today. So what are we gonna do with all the buildings that we have now that are not efficient, that are bad for the planet and so on. But also, home renovations were through the roof during the pandemic. Highest rate of home renovations in the last decade in the United States was in 2021.

Right? And so, We also cycle stuff in and out of our buildings at an alarming rate. We buy new furniture, we wait nine months for a couch to arrive these days, and then in a few years we’re done with it, right? And then it goes on Craigslist or on the sidewalk. And [00:05:00] so that stuff also adds up for carbon emissions.

So by 2050 interior renovations, whether that’s in your home, whether that’s in an office, will account for about a 10th of the world’s carbon emissions. So a lot of stuff that we think of as just beautiful like lights and chairs and rugs and carpets are also contributing to the climate crisis, and we don’t always think of that.

The building industry is the second largest consumer of plastics, and this fact may not mean anything in and of itself until you discover that. Plastic production is actually going to be the largest demand for fossil fuels by 2050. So when you think about oil and gas and fighting wars in the Middle East, and oil rigs, and oil spills and the Dakota pipeline and all that stuff around the fossil fuel industry, that anybody who’s interested in environmentalism or in climate change generally finds very problematic.

The thing is that all of that stuff is not going to be fought and [00:06:00] debated because we want to continue driving our cars. It’s going to be fought and debated because we want to continue using plastic stuff, and plastics are, and our industry, the buildings industry is the number two consumer of plastics.

So we are gonna be pretty implicated in that. Way more than the transportation industry or other industries that we think of as the forefront of the fight against climate change. And then 30% of household dust today is microplastics, right? And so we put all this plastic stuff in the spaces we’re in, and then it’s, it’s shedding microparticles, it’s putting out fumes. That stuff interferes with our living systems. There’s a study that came out last September that particulate matter in buildings can actually lead to lower cognitive ability, so like you’re actually getting stupider the more you’re around plastics.

This is unfortunately true, and so the way this stuff affects us and affects us through [00:07:00] buildings and through interiors is we’re still understanding it. Like there’s still new facts coming up all the time. And then this is again, maybe something you’ve not thought of, but. The number two industry for forced labor and labor exploitation is the construction industry globally, worldwide.

The International Labor Organization estimates there’s about three and a half million people who are working under conditions that violate human rights in the construction industry, right? And so we have these beautiful buildings we build, but somewhere along the supply chain, there’s always exploitation.

There’s scope for human rights abuses. And then of course, we’re not a very diverse industry. 80% of construction workers in the US are white and male, and about 22% of licensed architects in the US are women, right? And so there’s ways in which the human impact of our industry isn’t that great either.

And these things are interconnected. So the more we [00:08:00] have decisions in the building industry made by people who have money, who have ways to protect themselves from plastics in the air by buying purifiers or by investing in technologies, the more the harmful effects of what we do are gonna be passed on to people who can’t afford those things, who don’t have access, who don’t have the equal ability to survive the climate crisis.

And again, we know. Through our experience with the pandemic this past year, that whenever there’s a crisis, whether it’s a health crisis like the pandemic, which is fast and sudden, or like the climate crisis, it’s always the folks who are less privileged, who are going to bear the brunt. And so what can we do in the architecture and design industry to start to address some of the harm that we cause in the world, but also what can we do to use our work to do good in the world?

So I’ve spoken a lot about the harm, but John here is gonna talk about all the good that we can do. Which is the balance we need [00:09:00] today. So just a quick introduction to John. I already spoke about the things that Dattner does, but here are some wonderful facts. Dattner is responsible for about 8,300 units of a 100% affordable housing here in New York City.

John himself has been involved with many of those projects, absolutely fantastic. Some of the best affordable housing in the city. Was designed by Dattner. As I said, if you use the subway station in this city and if the subway station feels reasonably humane, chances are Dattner designed it. The first public LEED building in New York City, and for those of you who don’t know what LEED is, lead is uh, sustainability rating for buildings.

It takes a lot of different factors into consideration, including energy use and the first public building. Was designed by Dattner. What’s also wonderful is that it’s the Bronx Library Center, so in a borough that doesn’t always see a lot of investment in green building, Dattner has other amazing projects in the Bronx, which we’re gonna talk about, and then.

Close to a thousand passive house apartments. So passive house is a relatively new standard for [00:10:00] sustainability. What it means is that it uses only about 70% of the energy of a building that’s baseline, 70% less, but passive house standard actually grew up, was came out of Germany. It relies on really efficient buildings and making sure that building systems conserve energy through a variety of means, including insulation, access to daylight and so on and so forth.

So, Amazing work by Dattner that really addresses that broad range of impacts, whether it’s climate, whether it’s health, whether it’s equity in the city. And so super thrilled to have John here today. John, thank you so much for joining us. Great. Thank you.

John Woelfling: So you gave quite an introduction. Thank you for setting the stage with a preamble. It says we have a lot of work to do. The construction industry, I think has a lot of things that it can do better that have just kind of persisted because of momentum. So it’s gonna be hard to kind of wake us up from those practices. I think we have made some progress in the last couple decades, but there’s a long way to go.

And I think the work that I’d like to show you today is just a slice of that, [00:11:00] and it’s such a big, complicated problem that I think it’s not something that any one firm or any one piece of the industry can really address. It’s gonna have to be a really big, multi-layered solution.

Avi Rajagopal: I mentioned the Bronx Library Center, so I’m gonna start with that.

It was the first public building in New York City to be LEED certified. That’s all it was in 2006, so over 15 years ago. Tell us a little bit about how your approach to responsible architecture has evolved since then.

John Woelfling: So first of all, what I’d like to do is highlight one of the things that’s special about this building.

It took the idea of a traditional library and just completely turn it on its head. This building is very open, very glazed. A lot of daylight comes into this building, and that was one of the sustainable strategies is to use that daylight. To provide natural illumination to the interior spaces, and that was one of our sustainable strategies that really was a response to [00:12:00] local law 86.

Local Law 86 is a New York City local law that requires publicly funded buildings to comply with the LEED system. As mentioned, the LEED is a framework. It’s actually a very broad framework that looks at materials, looks at energy efficiency, water conservation, indoor air quality. It’s taken a little bit of kind of criticism for focusing on things like bike racks, which are kind of superficial, but it really was.

Back in 2006, I think the standard that helped the building industry really get a handle on how we could do better buildings and maybe a little bit to leads detriment or maybe to its benefit. It kind of became a marketing strategy where for-profit developers that were trying to encourage people to buy or rent in their buildings, they would promote their buildings as LEED certify, LEED gold, LEED platinum.

So I think it really was a key tool within [00:13:00] the free markets to advance sustainability, but it really was a very broad way to apply those standards. I think what’s occurred in the last 15 years is that we’ve gone from this market-based broad strategy to something that’s much more focused on carbon, and I think carbon in a couple ways.

Embodied carbon, what it takes to build a building, which you mentioned earlier, which I think we’ve got a lot of work to do. And then also operational carbon, what it actually takes to operate a building. We’re in a building that’s, you know, very comfortable right now, is being cooled. It takes energy to do that.

And there’s many ways you can do that. You can do it in a very wasteful way. You can recover some of that energy and some of the projects I’d like to show you today are using that energy in a very efficient way. I’m gonna try not to geek out on you. I may do it anyway and you just have to go along with me.

But I think what’s happened in the last 15 years is that we’ve gone from this market based system to something that’s much more regulated by. [00:14:00] New York City threw a couple things. There was local law 86 that I mentioned, which required this building to do a LEED certification. I got LEED silver, but there’s also more current things like local law 97, which is to really restrict a buildings of certain size restrict its.

Greenhouse gas emissions. There is some real complications on how the rubber meets the road on that legislation, but it’s a real significant advancement in New York City taking a real leadership position in how we meet our goals by 2050 to have a much more reduced carbon footprint in the city. So that’s one piece of legislation.

Another one is local law, 92 and 94. Which requires many buildings in the city, new buildings to do either a green roof or solar panels. There’s also, you may have heard the natural gas hookup ban, which applies to certain types of buildings as, and it’s gonna phase in over a period of time. So there are these legislative things that are happening within city government, which are adopting, I think, these best [00:15:00] practices that came about from LEED and are really starting to push everybody to being more sustainable just from a, a regulatory basis.

Avi Rajagopal: Yeah. And two administrations in this city have renewed their commitment to a, you know, a NetZero future for New York City, and as one of the world’s dense and built up cities, that’s going to be a huge task. Unless we use those levers to bring every building up to speed.

Dattner, you’ve also, you know, over the years, built this amazing portfolio of housing projects. You were joking earlier that you know, maybe somebody has even encountered one of your housing projects. What draws you to housing as a typology? Why is housing so important in this larger question of how do we make cities that are.

More climate friendly, healthier, more equitable, and so on and so forth.

John Woelfling: So since our firm is founding in 1964 by Richard Dattner, we have [00:16:00] worked in civic architecture and we’ve actually, we, you may call it civic architecture. We call it essential architecture. It’s architecture that is essential. For a city like ours to operate and operate in a functional way.

It’s providing green space, it’s providing mass transits that is beautiful and functional. It’s providing housing that is healthy and is really providing a stable place for people to live. I, you know, I, there is the statistic of the number of unhoused people in the city. It’s like 60,000 people, and many of those people are families.

I can’t imagine trying to do homework when you don’t have a place to call your home. It’s just, it is a thing that just. Undermines our society to such a detrimental degree. How are people gonna do their homework? How are they gonna become properly educated? How are they gonna become productive people in our society?

So it’s one of these things that I think our [00:17:00] firm feels is so important for our society to function properly. To have affordable, stable housing for a wide range of people and that distributed throughout the city. It can’t just be in one area. It’s gotta be distributed throughout the city. I also think that one of our important focuses in the office is environmental equity, which I think we can talk more about that later.

But there is, I think, an importance to have housing and infrastructure distributed fairly throughout the city. And I think some of our work is proactive in that regard, and some of it is kind of reparative. Which I’ll talk maybe a little bit more later, but I think our firm gravitates towards affordable housing because it really is something that’s an investment in the future, an investment in equity, and an investment in really making our city function the way it should.

Avi Rajagopal: Why don’t we talk about environmental equity now? It’s not something we’re used to talking about a lot. Like we tend to think about the environmental movement, energy efficient buildings. [00:18:00] For instance, let’s make New York City net zero as quite a different goal from. Let’s make sure everybody has housing and that nobody you know, is on the streets.

Like those two things are not often talked about in the same breath. So tell us about this concept of environmental equity or environmental justice and how your firm is involved in that.

John Woelfling: So since our firm does subway stations, we do marine transfer stations. Marine transfer stations is a way to move garbage outside of the city, and it’s a way to take garbage trucks.

From doing so much travel. When you can containerize garbage, you can deal with it in a way that has less carbon footprints. So one way environmental equity can be achieved is having these infrastructure items throughout the city. We have a marine transfer station up on the upper East side if those neighbors fought that tooth and nail, but we still have it up there.

We have it because, It makes sense to have these things distributed. So that’s one way that environmental [00:19:00] equity can be manifested. Another way is up on the, uh, on the west side. There is a pier that’s being renovated right now. It’s the gansevoort pier that is gonna become an outdoor public space. It used to be a Department of Sanitation, place to store salt.

We were able to create a new garage down in Tribeca on Spring Street. That was a place for some of the facilities that were at the gansevoort pier to come down. It’s a salt. Yet if you’ve gone down the West Side Highway, I’m sure you’ve seen this thing. It is a beautiful, sculptural, amazing piece of architecture that has one function to store salt, but it’s part of this environmental equity that I think we feel is so important in the firm.

So this project is in the Mott Haven section of the Bronx, and we got this commission through a New York City. Rfp, request for proposal. If I start speaking in abbreviations, slap me on the leg or something, correct me. I do take a lot of shortcuts, but the rfp Request for proposal was something that [00:20:00] was issued by the New York City Housing Preservation Development Departments.

They are the local agency that advocates for affordable housing, subsidizes affordable housing, and made this project possible. It was on a city owned lot that’s in the Mott Haven section of the Bronx. And if you know anything about the Bronx, it’s got a lot of environmental inequity. The asthma rates for children in the Bronx is the highest in all the zip codes in the country.

So this is a project that our developer client, Trinity Financial, wanted to, as part of the solution, as part of the proposal. Address this condition, and we did this through creating a 26 story, passive house building and passive house. I will, this is where I’m gonna maybe get a little geeky, but I’ll try to delay that as much as I can possibly.

The passive house strategy, as Avi mentioned, brings down your energy consumption by 70%. What that does is it allows the building to have less emissions associated with it. There’s also a high degree of filtered air [00:21:00] that comes into this building. The ventilation system uses something called an energy recovery ventilation, ERV.

That’s another one of my abbreviations. An ERV system to reclaim the energy that is in that conditioned air. When you, when, like in this space that we’re in, that’s air conditioned, that air can either be thrown away when it’s done, when you recycle it through the system, or it can go through something called an ERV, an energy recovery ventilation unit that takes that cooled air and tempers the incoming fresh air and brings it.

From, you know, the outside air temperature of 80 degrees to something more like 70. It’s a high efficiency way of reclaiming that energy that you’ve invested in that air. That also has some primary and secondary benefits of it. The primary is that you’re reducing your energy consumption. The secondary is that air that comes in is highly filtered.

So in this area of the Bronx where we’ve got the Major Deegan, we’ve got the Bruckner, we’ve got [00:22:00] Metro North Train that goes right by the site, a lot of air pollution, we are addressing that environmental inequity through our passive house building by providing that filtered indoor air. That I think make a dramatic difference to the 277 affordable housing units.

That’s gonna be the new home for, you know, 277 families in the South Bronx. So that’s an example of kind of reparative strategies that I think passive house can be a real example of. There’s another project in here, maybe I’ll talk about it later. That is a another way to leverage that building typology, but I think I’ve gone geeky enough for now. I’ll hand it back to you.

Avi Rajagopal: Deep Green will be back after a short commercial break.

I think it’s so interesting that there’s these details in buildings that have these multiple [00:23:00] benefits, right? Something that saves energy. But also provides clean air in, I didn’t know this, by the way, a zip code that has the highest asthma rates among children. Right. So that’s a powerful, that’s such a powerful strategy.

And it’s employed through a building. Right. And I think that’s what excites me about the practice of architecture. I think that’s what excites. Some of the folks who are in the sustainability building movement is that we can achieve so many different goals through some of these design strategies. And yet when you talk about the intersection of climate and equity, and even though as I was pointing out, that buildings are responsible for such a large section of the carbon emissions and we do influence equity in this amazing way, architects are not always thought of as the experts on these topics. Right? So what I’d love to hear from you is, you know, you work with city agencies, you work with policy makers, you work with all kinds of folks. How have you built up. A voice at the table and [00:24:00] what can we do as, as folks in the architecture world, or those of us who love architecture to see it become more of a force for creating change in the world.

John Woelfling: So I think the way that we can, the way that architects can start to move the needle on this is. Look for opportunities where you can with very little cost. And, and don’t get me wrong, passive house has a premium associated with it, and that premium I think is coming down. But on a project like this where it’s built right next to a subway station or right next to a subway line, there was a, an incentive, or there was a requirement to provide a high performance envelope, meaning it had to be highly insulated for acoustics.

We also couldn’t be poking holes in the wall to provide mechanical systems, so it really pushed us in a direction where we were basically halfway to passive house already. So it was a very easy pitch [00:25:00] for us to go to the client and say, you know what? We’ve got this high degree of installation that we need to do.

We need these high performance windows. We can’t be poking holes through the wall. Let’s try to do passive house here. And that was enough to convince them to really make the leap of faith. So this is another 248 units of workforce housing in the sound use section of the Bronx. It’s got, as you can see, solar panels on the roof.

It is gonna be an exemplary building, high health. One of the other benefits of passive house, because we’ve got this high performance envelope, is that the interior is very quiet. You don’t get all that airborne noise. And it’s especially important for something like this where you’ve got an elevated train that’s going by at a relatively frequent, so I think this is an example of how architects can start to make a difference, look for those opportunities.

I also think that in urban centers, especially in New York City, a lot of the easy sites to develop are already done. Those like [00:26:00] regular square, no brownfield, no contamination, not next to a, uh, an elevated train or a, a highway. Those are all done. What our office specializes in taking these really hard to develop sites, whether it’s weird geometry, elevated train, whatever, and make them into a piece of architecture about the place.

One of the things that we did on this project, which was when we came up with the idea, the clients just like beams. It was one of those really satisfying moments as an architect when we came up with this idea of these color panels that were something that you could see as you were approaching the building on the elevated train.

When she saw that, she said, oh, this is the happy scheme. That made me happy. But it was one of those like great moments where I knew I connected with my client and this was gonna be a long-term investment that they were on board with. When I think about, you know, deriving a great deal of satisfaction from what I do, this is an example of that, and that moment was a real estate.

Avi Rajagopal: [00:27:00] No, so much of this lies in kind of that partnership you have with your clients or with the agencies you work with or whoever that might be. Talk to us a little bit more about how you’ve managed to build some of those partnerships and push the envelope, right? Like whether it’s the Bronx Public Library, whether it’s this building or via Verde, which I know is here, which was a landmark project.

You should talk a little bit about Vi Verde as well. How do we get folks who are traditionally risk covers, understandably so. They work with limited resources. They want true and tested methods. How do you work with them to invest in something that you know is future proof, but they don’t know yet?

John Woelfling: That is a really good question and one example is the, the local law that I just mentioned, local law 97. Local law 97, is gonna phase in over time. And require certain performance standards as we age into the program. [00:28:00] And the first threshold, I think is in 2025 or 2027, not that far away. It takes a year to design a building. It takes two years to build it.

That’s three years. If we’re designing a building now, it’s not gonna come online until 2025. Why would you design a building that you know, either when you bring it online or two years later, is gonna need to replace a system that is gonna be emitting too many greenhouse gases? So one of the things that we’re doing with our clients is educating them to these new regulations.

And even, you know, you shouldn’t just be looking at when the building’s gonna open, or a couple years. The systems in these buildings have a lifespan of decades. So why would you replace a system 10 years into its lifespan when it has another 10, 15 years and its usable lifespan. So it’s us, I think alerting our clients to what is just down the road.

[00:29:00] And you know, electrification is another big thing that we are, we’re having to do in the city. And I think one of the things that we need to do as a state, is improve our grids resiliency and frankly, the cleanliness of it. Downstate has very dirty energy, so because of all the Peaker plants that are with embedded within our communities, we need to be able to take those offline and we need to have more renewable sources.

Upstate that has better connectivity downstate. So that’s something else that’s, I think I want to help educate my clients and industry groups to understand that we need to be advocating for that thing. This project on the screen via Verde is one of our landmark projects. That was, again, one through a, a worldwide competition that was issued by HPD housing, the New York City Housing Preservation Development Department.

It was innovative in many ways. And this was done, I think this was finished in 2007, actually quite some time ago, but it had [00:30:00] home ownership. It had rental, it had integrated pv’s. It’s called Via Verde, the green way. It has this ribbon of space that that connects all of the buildings with this outdoor, passive and active recreation space.

It was really a phenomenal integration of sustainable design and building design and site design. The site is very complicated. It’s this weird triangular space. The zoning was complicated. I’m sure we got some Mayoral overrides to make it work, but it was one of those real partnerships between not only our clients but the city as well to really make this project happen.

There were other things that had to happen upstream of this to make it work, but it was one of, it was an example of how when you’ve got the right players at the table, you can make a phenomenal project.

Avi Rajagopal: You’ve spoken at length about some of the strategies you’re using in current projects that have multiple benefits.

I think the erv example is my favorite so far. System that is low energy, but at the same time [00:31:00] provides clean air and buildings. Amazing. What are you working on now at the firm? What are some of the things you’re trying out or hoping to try out in projects that might have some of those kinds of benefits?

John Woelfling: So this is a project that we have just recently started on. It was a commission that we won through HCR. HCR is Homes and Community Renewal. It’s a New York State organization that’s that advocates and promotes affordable housing throughout the state. This was a 28 and a half acre site in East New York.

It’s near the Gateway Shopping Mall. It used to be the Brooklyn Developmental Center, which was a series of one story buildings for people who had developmental disabilities. That model has aged out of practice, and those clients are elsewhere throughout the city. So this site became an opportunity to redevelop it as a completely new and dense housing center.

So our developments team, which is a combination of four different clients, wanted to do [00:32:00] something that was. Innovative, I mean like really innovative and, and because of the site of this, we were able to do this really comprehensive plan. Many of our projects are just like a site here, a site there, and there isn’t this like large community, this is gonna be 2,400 units.

Of housing that is large enough that we can do things like a central gardening facility. We can do geothermal, we can do this idea of a 10 minute neighborhood. We’re creating enough building here that we can create this walkable neighborhood that has retail. It’s got community facility, it’s got housing, it’s got the urban farming that I mentioned, that urban farming is one of our clients.

Riseborough is very invested in this idea of restorative gardening as a therapy for some of their clients. So we’re able to do that here. So in addition to all of those benefits that come from this 10 minute neighborhood of being able to walk and less reliance on cars, we’ve got that restorative aspect of it.

We’re [00:33:00] creating a community that’s walkable. All of these buildings are gonna be passive house buildings. So again, reducing that energy. It is in a flood prone area, so we are actually raising the site to look down the road and anticipate increased storm surge. It’s also just on the other side of this road that you see here, there is a Parkland, that’s New York State Parklands.

So, great access to outdoor, urban green space within the community. So it really is, I think, a, a phenomenal project that because of its size, it can do these tremendous things. This is kinda like a once in a career opportunity. So we are very fortunate to have something like this in our office. There’s even like a, a, the little gray box that you see in the corner that’s gonna be an SCA school.

So it really is this idea of a 10 minute neighborhood. Everything is right. There you can access bus lines if you wanna get further out, away from your neighborhood to go shopping or whatever, but it’s, it really is this phenomenal project that is, that’s very dense. And I think that’s actually, that’s one of the [00:34:00] key things about buildings in New York City.

There is this density that we can achieve here that makes passive house easier. When you’ve got hundreds of people living in the same building, there is this dynamic that happens with that density, that density of bodies, that density of appliance use, that density of lighting. Passive house really means that you’re heating or cooling the building in a more passive way.

So the, the reason why you can reduce that energy consumption by 70% is because you’re taking advantage of all that internal heat gain from the bodies, from the appliances, from the lighting. So that’s where a lot of that efficiency comes from. That efficiency is then coupled with a tighter envelope.

And that tighter envelope really means that you need to have that energy recovery ventilation. You’ve gotta improve the ventilation within the building, or you’re really gonna have problems with the indoor air quality. So passive house is this system that has all of these interrelated things come together.

And you gotta do ’em all right? [00:35:00] If you say, oh, you know what, let’s cheat a little bit on the, on the ventilation. Let’s not ventilate it quite as well, or at quite as high of an efficiency. The whole thing starts to unravel where you might get condensation in your walls, you might have sick buildings. So it is taking this idea of building buildings and ramping it up a notch, making them more complicated, but more energy efficient.

I think that’s one of the other things that for us to do the right thing, we’re gonna have to be a little bit more courageous. We’re gonna have to take on these bigger challenges and do them, we’re gonna have to take it seriously.

Avi Rajagopal: You mentioned the advocacy that we all need about having a better energy grid and so on. If you had to take things that you wish the clients you interact with or the people who occupy our building, were just a little bit more aware of, what would it be like? What would you like to say? Hey, we need to expect more from our buildings. This is what we should expect.

John Woelfling: I think it’s a combination of courage and also just looking at the return on [00:36:00] investments, which I actually can’t believe that this is something I’ve gotta remind some of my clients about.

The 425 Grand Concourse Project. Our clients, Christoph Stump, made a presentation recently, I forget the venue, but he said that because of this building’s energy performance, they’re gonna save. Six to $700,000 a year on energy costs. That is some real money, and it would only, I think he said it would take like two or three years to recoup the investments, the premium that they paid for this building, the premium that they paid for, the soft cost.

The cost for a special consultant to do the passive house strategy was paid back in such a short period of time that after that initial return on investments, it’s now just money in their pockets. So to me it seems like a no-brainer. So I think it’s having a little bit of courage, a little bit of faith, and then looking at that return on investment and really, Undertaking that, you know, a little, amping it up a [00:37:00] little bit.

Having the courage, having the faith in your consultants and the faith that you can deliver a, a, a high performance building. That’s, that’s what I hope I can convince my clients of and the rest of the industry can do as well.

Avi Rajagopal: Yeah, I mean, whether we’re renters or homeowners, whether we’re architects or folks who operate buildings, we’re all in a race against time now, and so thinking about that return in investment is so important because, Once we hit the say 2030, 2040 mark, which is where the United Nations and everybody else is kind of stake their flag once we hit that point.

It’s not just that having a less efficient building or a less equitable building is going to be more expensive, it’s going to start costing exponentially as well in terms of it’s going to be a liability. Frankly, right. Whereas on the flip side, making the investment now only sets you up for savings and a, and a high return investment.

So it’s not just that you’re notionally saving that money in the pocket, you’re also ensuring against [00:38:00] the future. That honestly looks a little bleak. Sorry to bring us down again at the end of this conversation, but the cost of doing nothing is so high and the savings of doing something are so high that it seems like, you know, we should all be on this path.

If you want to discover more of Metropolis perspectives on sustainability, head on over to metropolismag.com. Deep Green is a proud member of the SURROUND podcast network. Discover more shows from [email protected]. This episode of Deep Green was produced and edited by SANDOW Design Group.

Special thanks to the podcast production team, Hannah Viti, Wize Grazette and Samantha Sager. The 2023 season of Deep Green will be available shortly wherever you get your podcasts.[00:39:00]